I tend to ramble on about topics that interest me. I can chase after the conversational thread of a miniseries I found, a song I’ve been obsessed with, the works of an author I admire. Even if I’m not always sure where it will lead me, I’m always ready to run. With my parents being the greatest sufferers of my need to talk, they were the ones who gifted me this site. Obviously, I was thrilled to be able to finally have a proper outlet – at last, I could rant/rave about books, movies, TV shows – anything about which I felt so inclined!

The first hurdle came in finding a name for my newfound blog. I suggested my first idea to my parents – “Athenium.” It’s often used as a synonym for “library,” and I love Athena, so wouldn’t it fit?

But I understood quickly that the name was too simple, too common. The more I thought about it, it felt a bit too official for my liking.

“What if you used an item from mythology?” my mom brought up. “Like the Golden Fleece?”

From that spark, my dad was the one to suggest “Atalanta’s Apple.”

“It was like a distraction for her, wasn’t it?” he said. “And aren’t your books and movies distractions too?”

I hesitated. “Well, yeah. But it wasn’t a good thing that she chased after the apple – she lost the race.”

“But didn’t she get married at the end?” my dad asked, as if that was the best thing she could’ve hoped for, her guaranteed happy ending.

“She never wanted that,” I started to explain, but he held up his hand before I could delve into Atalanta’s journey. “Blog it,” he told me.

So, I did.

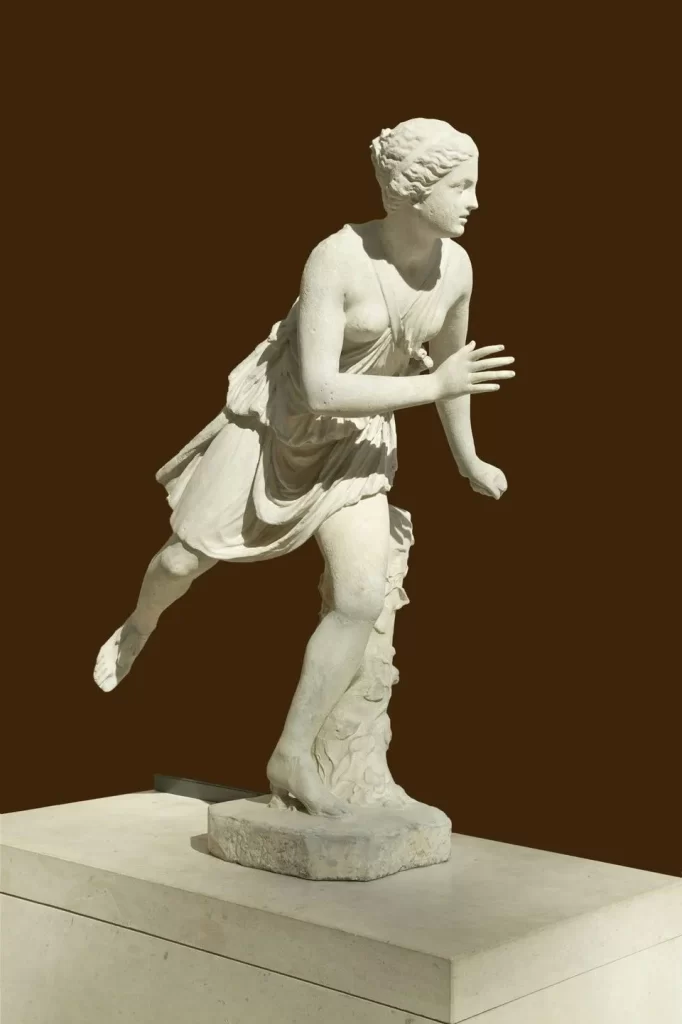

Atalanta of Arcadia. Most known for her iconic race and the golden apples –

Okay, that’s enough. This isn’t a Wikipedia article.

Atalanta might be most known for losing her last race (although she won dozens before), but there is more to her story than the cursed golden apples that always follow her name. It began when she was a baby, cast out by her father for the audacity to be born a woman. But Atalanta, already destined for great things, was not meant to die on that forested mountain. A she-bear, whose cubs had all been killed by hunters, found the baby Atalanta. Two creatures who had been denied their birth family formed their own. And this is how Atalanta grew.

There was a point at which Atalanta was discovered by hunters, who taught her more human customs. But for a girl who was always so wild, so free, so strong, there is a part of her that must have never forgotten her days as a bear.

In what was either the greatest opportunity or the worst mistake of her life, Atalanta stepped out of her forest to participate in the Calydonian boar hunt. Many men had rallied together to slay the creature that was ravaging their lands, but Atalanta was the sole woman.

Reaching a turning point in her life, Atalanta stepped across the Rubicon and let herself be open to the judgment of humans for the first time.

This hunt was led by the prince Meleager. When he saw Atalanta, he fell for her instantly – but sources debate whether it was out of genuine love and admiration for her talents, or Meleager’s desire to father a child with Atalanta. Which must have been the greatest disappointment, had Atalana returned his affections. “A child,” they say, but they really mean “a son.”

Atalanta struck the first blow against the boar, and Meleager was the one to slay it. But he gifted the pelt to her, insulting all of the men who had hunted alongside them. Meleager’s death was a result of the ensuing fight, and Atalanta’s story continued onward.

Whether she loved Meleager or not can certainly be brought into question. But although her human name, Atalanta, meant “equal in weight,” Meleager was the first to treat her as an equal among humans – even above certain men, given how he gave her the boar’s pelt.

Finally accepted into her human family – the king who sent her out to die – Atalanta was persuaded to get married. After all, if she was to be a princess, she must have a prince.

So she made the deal that would preserve her future. Equal in name only, Atalanta made a proposal to any of her potential suitors. In exchange for her hand, they must beat her in a footrace. The losers would be killed.

Atalanta, the huntress who was raised in the forests, continued to be her wild, natural self. It could be argued that she set up the infamous race out of love for her dead Meleager, if she ever felt that way about him. But was that really the love strong enough to determine her future, the love that would save her future?

It was her love for her childhood wilderness that she defied her parents for. Could there be anything greater for her to discover?

Men came and never left. Time and time again, Atalanta bested every suitor who thought they could outmatch her. She never backed down, never gave them an inch, never showed any mercy. No man would keep her from her freedom.

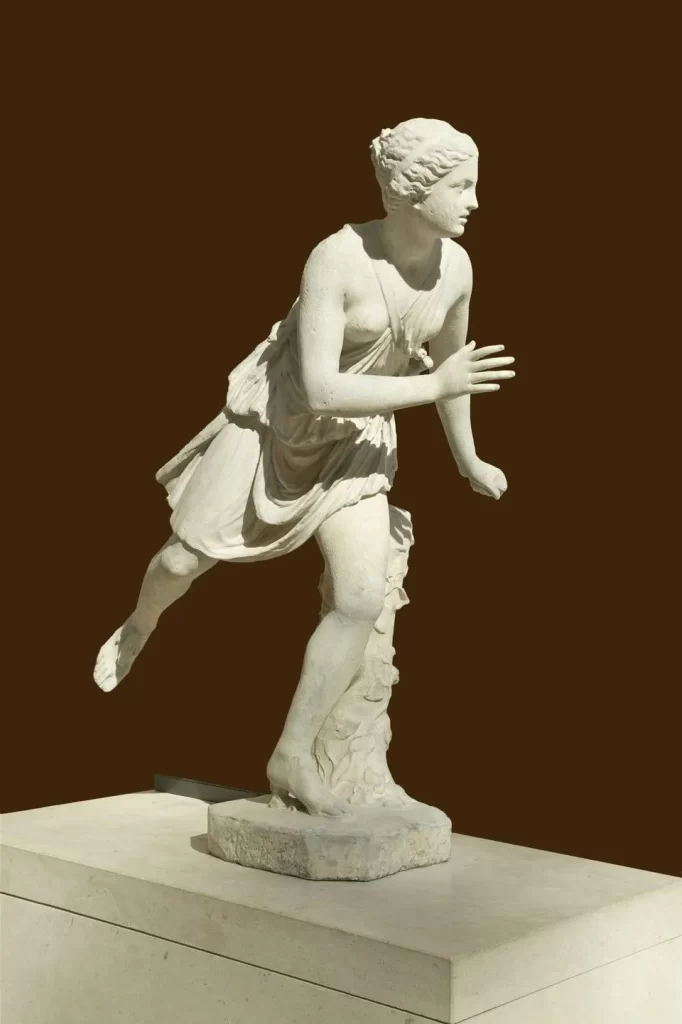

But it can be argued that Hippomenes, her latest admirer, was different. He fell in love with Atalanta the moment he saw her. More humble than the rest, Hippomenes turned to the goddess Aphrodite to request her assistance in winning Atalanta’s race. She bestowed upon him three golden apples, and the rest is history.

There are three different ways that I’ve heard the story of Atalanta’s apples before. The first, the most common, is that she was enchanted by the golden fruits and chased after them, forgetting all about her race. Maybe any person would’ve been written this disappointingly, but I never liked the fact that the end of this woman’s strength didn’t come from a worthy rival. I was insulted that Hippomenes would expect Atalanta to fall for such a trick, and I was insulted that Atalanta fell all the same.

But I recall a version I read in an old book of mythology when I was a kid. The apples weren’t merely gold; they were magical. I remember so vividly the descriptions of what Atalanta saw as Hippomenes threw the apples – visions of her days as a bear-child, the thrill of the boar hunt. And then the last one, the most powerful one, the one that came right at the end. Hippomenes released the apple, and all Atalanta saw ws Meleager. Meleager hunting at her side, Meleager gifting her the boar pelt, Meleager dying before her –

Atalanta regained consciousness, the final apple in her hands, tears running down her face. She turned, and Hippomenes was walking towards her, ready to claim his prize.

I remember exactly where I was when I read this story. I was in the mall, waiting for my mom outside of a clothing store. I had been reading this to my little sister, and we were both speechless. “Is that the end?” she asked after a moment. I just nodded.

That’s the second version. The third one is the most modern one, the most feminist. It’s the concept that Atalanta wasn’t beguiled by gold or memories, but by Hippomenes himself. She loved him as much as he loved her. So she just happened to take long enough to seize the apples that she allowed Hippomenes his victory.

I wonder, is that better than the story that came before? That Atalanta’s loss came from the love of a living man, not a dead one? Must her story always be defined by the men in her life, by their love?

Atalanta did not break her word. As per the rules she set up, she and Hippomenes were promptly married. It was through a trick that he was able to win her hand, but did Hippomenes ever win her heart?

He could not defeat her with his own abilities, but maybe Atalanta would’ve admired that. He held no delusions of his own skill – he knew, if he were to best her, it would be in an area far beyond her reach. Why did he take such extreme measures? Did he want the glory of claiming the uncatchable princess? Was he like every other man in her life, determined to show her that she could be beaten? Or, perhaps, did he simply love her? Would she have come to love him?

Just as Atalanta’s tale never began with the race, it does not end there either. This is the last stage of the story.

Atalanta married Hippomenes, and the two of them, while out hunting, found themselves in a temple to Zeus. Maybe, according to one account, it was a curse of Aphrodite that caused the couple to become overcome with lust, but why should that be the reasoning? Why must all of Atalanta’s actions be set by outside forces? Is it so difficult to believe that she had truly fallen in love with Hippomenes, that when she had sex with him in a temple it was her own doing?

Either way, the result is always the same. For their defilement, Atalanta and Hippomenes were transformed into lions by the gods, never to be human again. The rest of their days were lived out as tameless beasts, fanged and clawed, entirely separate from the world of mortals.

And was that such a curse?

Atalanta never returned to her father’s kingdom, but she came home. In the end, she returns to the wildness of her childhood, the freedom of the forests, and the hunt.

I like to imagine Atalanta’s true mother, the she-bear, wandering through the trees. She is older and slower, but she is still strong. While she is on her hunt, she spots an imposing figure in the distance, muscles lean under rippling fur. She approaches the jutting rock cautiously. The eyes of the golden-haired lion meet her own, and the she-bear knows that her daughter has returned.

Atalanta’s legend exists forever in the human realm, but she must have thrived far greater in the wilderness. The bear-child girl, finally returning to her roots, free from the mortal restraints that tried and failed to hold her. And not alone – with Hippomenes at her side, always.

It was with Hippomenes that Atalanta continued to hunt as a human. It was through him that the both of them threw all caution to the wind and sealed their fates. Did Atalanta love him then? Did she trust him? Did she know that he would lead her to her true destiny?

Hunting as a lion in her forests – she must have never felt more free.

It can be argued that, in many of the milestones of Atalanta’s life, she was without agency. Maybe that is why the third version of Atalanta’s story is the most accepted. We want to believe that Atalanta made her own choice when she ran after that apple. But really – what was she chasing? A shiny prize? Her dead prince’s voice? Or Hippomenes’ guaranteed victory over her?

It was through Hippomenes that Atalanta was finally married. It was through Hippomenes that she defied the gods in a sacred temple. It was through Hippomenes that she returned to her forest in the end.

Maybe it wasn’t just the apple. Maybe Atalanta was chasing the promise of Hippomenes’ devotion. She was running after what she knew he could give her, what they could achieve together – a love that would spur them to defy the gods.